Here’s what you’ll learn when you read this article:

- GLP‑1 and dual agonist drugs like tirzepatide have shown the ability to slow tumor growth in obesity‑linked cancers, especially in preclinical models.

- Early human data suggest a potential reduction in cancer risk among GLP‑1 users, though no trials have confirmed treatment effects in cancer patients.

- These medications may influence cancer progression through both weight loss and direct modulation of tumor or immune pathways, but more research is needed.

The link between excess body fat and certain cancers continues to emerge as a major public‑health issue. Obesity triggers metabolic disturbances—hormonal shifts, insulin resistance, chronic inflammation—that can foster tumor initiation and progression. Drugs originally developed to treat diabetes and obesity now show unexpected promise at the intersection of metabolism and oncology. Among them, dual GLP‑1/GIP receptor agonists such as tirzepatide stand out. New preclinical data suggest these agents might do more than slim waistlines: they may slow the growth of obesity‑associated cancers. Fountain of Youth explores that evolving evidence, examines its limitations, and outlines practical ideas for patients and clinicians alike. Our team at Fountain of Youth SWFL monitors such developments closely to ensure our content reflects the most current science.

Why Obesity and Cancer Share a Dangerous Path

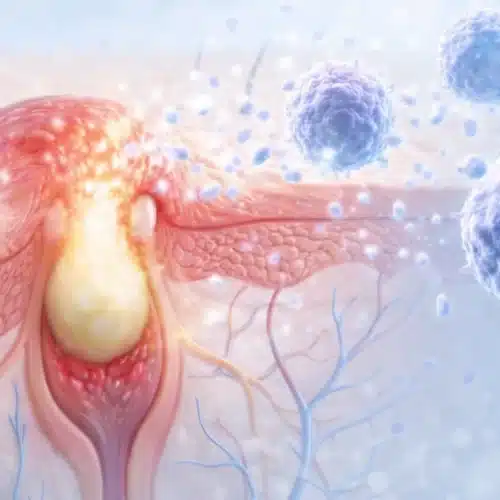

Carrying excess adipose tissue disrupts metabolic balance in multiple ways. Fat tissue secretes hormones and inflammatory molecules. Elevated insulin, altered sex hormones, and systemic inflammation create an environment that can encourage cellular proliferation and impair normal cell death. Chronic metabolic dysfunction heightens cancer risk and often worsens prognosis for cancers such as breast, endometrial, and colorectal. Treating obesity solely as a weight problem misses how deeply it influences cancer biology. Recognizing obesity‑related cancers as a unified challenge opens the door to new, metabolism‑focused strategies. Traditional weight‑loss methods often fail to deliver long-term change. Diet, exercise, and behavior modification can succeed temporarily, yet many people struggle to maintain fat-loss over years. Metabolic drugs—initially designed for diabetes or obesity—now appear capable of reshaping body composition and metabolic milieu. This raises a question: could pharmacologically altering metabolic dysfunction also suppress obesity‑associated tumor growth?How GLP‑1 and Dual Agonists Operate: More Than Appetite Suppressors

GLP‑1 (glucagon‑like peptide-1) receptor agonists and dual GLP‑1/GIP (glucose‑dependent insulinotropic peptide) agonists work by mimicking gut hormones that regulate appetite, insulin secretion, and energy balance. Clinically, they slow gastric emptying, increase satiety, reduce caloric intake, improve glucose tolerance, and lower insulin resistance. Over time, they trigger meaningful fat loss and metabolic improvements in many users. Beyond improving metabolic health, these agents could exert “onco‑metabolic” effects—altering the biochemical and hormonal environment that cancer cells rely on. Lower insulin, decreased adipose-derived inflammatory signals, and improved lipid profiles may reduce proliferation signals for tumor cells. In that sense, GLP‑1–pathway drugs might indirectly influence cancer growth by reversing metabolic conditions that favor malignancy. Dual agonists like tirzepatide also modify fat distribution and systemic metabolism more profoundly than traditional treatments. Their impact on insulin, lipids, and adiposity prompts renewed interest in testing whether they can break the obesity–cancer link in both preventive and therapeutic contexts.Evidence from ENDO 2025: Tirzepatide Slows Breast Tumor Growth in Obese Mice

Researchers from the University of Michigan presented a preclinical study at ENDO 2025 showing how tirzepatide slowed obesity‑associated breast cancer in mice. The study involved 9‑week‑old C57BL/6 female mice fed a 40–46% high‑fat diet and housed under thermoneutral conditions to induce obesity. After 32 weeks on that diet, the mice received tirzepatide injections every other day for 16 weeks, while control mice received placebo. Investigators implanted triple‑negative breast cancer cells (E0771) to simulate obesity‑driven mammary tumors. Treated mice lost around 20% of body weight, largely from reductions in adipose tissue. Investigators observed significantly smaller tumor volumes in the tirzepatide group compared with controls. Tumor volume at study end correlated with body weight, total fat mass, and liver fat content, suggesting that reductions in adiposity tracked with slowed tumor growth. The authors concluded that tirzepatide “may play a beneficial role in the reduction of obesity‑associated hormone‑dependent tumor growth.”Evidence Beyond Breast Cancer: Colon, Endometrial, and Broad Metabolic Models

Researchers extended the tirzepatide investigation to other obesity‑linked cancers. In one preclinical model of endometrial cancer, tirzepatide treatment over four weeks reduced tumor weight by more than 60% in obese and lean mice with LKB1/p53 deletions. Investigators observed lowered tumor cell proliferation (decreased Ki‑67), reduced anti‑apoptotic signaling (lower Bcl-xL), and downregulated metabolic and inflammatory pathways in treated tumors. The drug reversed obesity‑related alterations in glucose and fatty‑acid metabolism, lowered inflammatory markers, and modulated tumor‑intrinsic signaling, as shown in this Gynecologic Oncology study. In colon‑cancer models under diet-induced obesity, similar reductions in tumor acceleration emerged after tirzepatide treatment. Those findings suggest the effect might generalize beyond breast tissue, especially in tumors whose growth accelerates in obese metabolic contexts. The consistency across different tumor types implies that tirzepatide could broadly mitigate cancer-promoting effects of obesity. The mechanisms seem to vary by tissue type and tumor genetics, but the unifying theme remains metabolic restoration. Obesity has been linked to increased risk for at least 13 different cancer types, according to epidemiological data. The chart below summarizes key cancers associated with obesity, the average risk increase for each, and whether GLP‑1 agonist research currently supports a possible benefit.| Cancer Type | Estimated Risk Increase Due to Obesity | GLP‑1 Agonist Research Status |

|---|---|---|

| Breast (postmenopausal) | 20–40% higher risk | Preclinical studies show tumor suppression in obese models |

| Endometrial | 2–5 times higher risk | Multiple animal studies confirm tumor shrinkage and metabolic modulation |

| Colorectal | 30–50% higher risk | Animal models show promising tumor growth reduction |

| Liver (hepatocellular carcinoma) | 2 times higher risk | Human data sparse; indirect metabolic improvement may offer benefit |

| Kidney (renal cell) | 40–80% higher risk | No direct GLP‑1 studies yet; observational risk reduction reported |

| Ovarian | 10–20% higher risk | No preclinical or clinical data currently available |

| Pancreatic | 50–60% higher risk | Caution warranted; historical concerns about incretin effects on pancreas |

Untangling Mechanisms: Weight Loss Versus Direct Tumor Modulation

Interpreting these preclinical results requires distinguishing between indirect effects (weight loss, improved metabolism) and direct effects (impact on tumor cells or microenvironment). Weight loss reduces insulin resistance, lowers circulating insulin and IGF‑1 levels, and decreases adipose‑derived inflammatory cytokines. That cascade may remove growth‑promoting signals for cancer cells. Medical researchers often note that weight loss itself can yield favorable cancer outcomes. In the mouse breast‑cancer model, chronic calorie restriction produced stronger tumor suppression than tirzepatide, hinting that weight loss alone plays a major role. At the same time, tirzepatide appears to influence tumor-intrinsic pathways. In the endometrial cancer model, the drug suppressed markers like Ki-67 and Bcl-xL and altered metabolic gene expression, lipid signaling, and inflammatory mediators—even in lean mice. That suggests a direct pharmacologic effect beyond simple fat loss. Some researchers propose that incretin‑based drugs also influence cancer risk by altering metabolic-inflammatory signaling within the tumor microenvironment. This is detailed in the 2024 review published in the journal Cancers.What Human Data Show So Far: Epidemiology and Observational Trends

No clinical trials yet prove that GLP‑1 agonists shrink existing tumors. Human evidence rests on observational data about cancer incidence and risk. One large retrospective cohort study of over 1.6 million patients showed that GLP‑1 receptor agonists were associated with significantly lower incidence of multiple obesity‑associated cancers compared to insulin users. These associations persisted even after adjusting for comorbidities and other risk factors. A broader review published by PubMed Central in 2025 found no increased cancer risk associated with GLP‑1 agonists overall. In some cases, cancer risk appeared reduced—especially in patients with sustained metabolic improvements. Some cancer survivors with obesity now receive GLP‑1 therapy to manage weight and reduce adiposity-related recurrence risk, although no formal guidelines exist. Anecdotal reports suggest favorable tolerance and modest weight loss in these populations.Use in Cancer Patients Today: Promise, Precautions, and Unknowns

Oncologists and metabolic specialists occasionally prescribe GLP‑1 agonists for patients with prior or active cancer. Primary motivations include managing obesity, improving insulin sensitivity, reducing fatty‑liver disease, and optimizing cardiometabolic health. While some small series suggest tolerance and benefit, safety and efficacy remain unproven in cancer patients undergoing therapy. Cachexia risk, chemotherapy timing, and nutritional needs complicate decisions. Patients should always coordinate care between oncology and metabolic providers.Safety Profile, Limitations and Ethical Considerations

GLP‑1 agonists may cause nausea, digestive symptoms, and rare pancreatitis or gallbladder issues. These side effects pose concerns in patients already managing chemotherapy or nutritional vulnerability. Meta‑analyses, including the one in JAMA Oncology, find no increase in cancer incidence across populations using GLP‑1 receptor agonists. Overall safety signals remain favorable. Still, without randomized trials, using these medications as cancer adjuncts remains speculative. Off-label prescriptions must include informed consent and clear benefit-risk discussions.Three Practical Tips for Patients and Providers

Evaluate Your Metabolic Health as Part of Cancer Risk

Talk with your physician about how obesity, insulin resistance, and fat distribution might influence your cancer risk or prognosis. Effective weight management or metabolic optimization could serve as a meaningful part of long‑term prevention or survivorship strategy—even before considering medication.Interpret Headlines About “Weight-Loss Shots That Cure Cancer” with Caution

When reading media stories about GLP‑1 drugs shrinking tumors, look closely at whether the data come from animal studies or human trials. Note differences between “reducing risk” and “treating established cancer.” Ask whether experts emphasize preliminary findings or proven clinical benefit.If You Have (or Had) Cancer, Plan GLP-1 Use in Coordination with Your Care Team

Do not start or stop GLP‑1 therapy without discussing with your oncologist and metabolic specialist. Address timing around cancer treatments, nutrition status, and potential side effects. Ask whether ongoing trials or registry studies might offer you access to more robust data.Common Questions (FAQ)

Are GLP‑1 and dual agonists currently approved as cancer treatments or only for diabetes and obesity?

These drugs remain approved only for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Researchers did not design them as anticancer treatments. Existing approvals do not cover cancer therapy or prevention.If I am a cancer survivor with obesity, could a GLP‑1 agonist help lower my recurrence risk?

Observational studies suggest GLP‑1 therapy may modestly reduce incidence of obesity‑associated cancers compared with insulin or other diabetes drugs. Some survivors have experienced sustained weight loss on GLP‑1s. Because high body fat worsens prognosis, reducing adipose tissue might lower recurrence risk—but evidence remains indirect and non‑definitive.How do researchers decide which cancer types are most likely to benefit from GLP-1–based strategies?

They focus on cancers strongly linked to obesity or metabolic dysfunction—breast, endometrial, colon, and others. Preclinical models examine tumors whose growth accelerates under high-fat diet, insulin resistance, or chronic inflammation. Researchers also consider tumor hormone‑dependence, receptor expression, and microenvironment sensitivity to metabolic signals.What should I ask my oncologist before starting a GLP-1 medication while on cancer therapy?

You should ask whether metabolic benefit outweighs potential risks in your situation, how the drug might affect treatment tolerance or nutritional status, whether timing around chemotherapy or hormonal therapy matters, and whether monitoring plans exist. Also ask if any relevant clinical trials or registries include patients with your cancer type and treatment history.Caveats and What These References Do Not Provide

- None of the referenced studies prove that GLP‑1 agonists act as effective cancer treatments in humans. Most support risk modulation or prevention potential, but not definitive therapeutic benefit. Preclinical data in mice cannot fully predict human outcomes.

- Observational human data cannot establish causality. Lifestyle, comorbidities, and concurrent treatments may influence results. Meta‑analyses provide insight, but lack the specificity of prospective trials.

- Weight loss, not the medication alone, may account for some benefits. Without trials comparing GLP‑1 drugs to other weight-loss strategies, definitive conclusions remain out of reach.

Medical review: Reviewed by Dr. Keith Lafferty MD, Fort Myers on December 5, 2025. Fact-checked against government and academic sources; see in-text citations. This page follows our Medical Review & Sourcing Policy and undergoes updates at least every six months. Last updated January 3, 2026.