Why the initial assessment matters in medical weight loss

A medical weight-loss plan works best when it starts with clear baselines. The first visit sets a shared understanding of health priorities, while labs clarify hidden risk. Many people feel frustrated because effort rarely matches results, yet baseline data often explains that mismatch. Clinicians use this step to separate weight from complications, since complications drive urgency.

Baseline testing also helps avoid unnecessary testing later. A focused panel can flag diabetes risk, lipid problems, and liver strain early. Targeted endocrine screening can identify a true medical contributor, while broad hormone panels often add noise. Patients benefit when the workup follows symptoms, because symptoms sharpen what “baseline” should include. Clear baselines also make progress measurable without overfocusing on the scale.

What happens at the first visit

Intake paperwork that affects clinical decisions

Clinics start with details that shape both safety and priorities. Symptoms such as severe fatigue, heat or cold intolerance, or new bruising change which tests matter. Past weight-loss attempts also matter, since prior response patterns can suggest metabolic risk or medication effects. Family history of diabetes or early cardiovascular disease raises suspicion for silent risk.

A good intake also captures functional impact. Joint pain, shortness of breath, and sleep quality influence the “why” behind weight goals. Work schedules and caregiving demands can affect lab timing and follow-through. Stigma-free language matters, since shame blocks honest reporting and future engagement. Clinicians often ask for real patterns rather than perfect answers, since accuracy matters more than “good behavior.”

Medication and supplement review

Medication review belongs in the first visit because medicines can drive weight change. Some prescriptions raise appetite, change insulin sensitivity, or affect fluid balance. Over-the-counter products add risk too, since many “metabolism” aids contain stimulants or thyroid-active ingredients. Supplements can also interfere with hormone measurements, so clinicians should document them before ordering endocrine labs.

A careful review also prevents false alarms. A lab can look abnormal after a recent steroid course, a biotin-heavy supplement, or a new hormonal therapy. Clear documentation helps clinicians interpret results correctly, while patients feel heard instead of blamed. Clinics often ask patients to bring bottles or screenshots, since memory fails under stress. That step sounds small, yet it can prevent repeat bloodwork.

Lifestyle snapshot used only for baseline context

The first visit usually captures a short “real life” snapshot. Clinicians may ask about sleep timing, shift work, alcohol intake, and typical meal timing. People often expect a full nutrition plan immediately, yet baseline visits prioritize measurement first. Movement habits help contextualize resting heart rate and blood pressure readings.

Stress level also matters, since it influences sleep and food choices, while the plan can address it later. This snapshot supports interpretation, while separate pages can cover behavior systems and meal planning depth. The goal stays simple: capture the baseline conditions that shape labs and risk. A focused snapshot also reduces the chance of duplicating other support topics.

Baseline measurements clinics document and why they matter

Anthropometrics and body composition markers

Clinicians measure height and weight to calculate BMI, since BMI supports risk stratification. Many clinics also measure waist circumference, since central adiposity links strongly with cardiometabolic risk. A helpful clinical reference for this practice appears in the consensus statement “waist circumference as a vital sign,” which focuses on visceral obesity risk. Waist measures add value when BMI alone misleads.

A muscular person can carry a higher BMI with lower metabolic risk. A smaller person can carry more visceral fat, which raises diabetes risk. Many clinics also track waist-to-height ratio, although the exact metric varies by protocol. The key point stays consistent: baseline measurements support trends more than one-time judgments.

Some clinics use body composition tools, while others stick to tape measures. Bioimpedance can track fat mass trends, yet hydration shifts can move readings. A baseline reading still helps, since future readings use the same device and conditions. Patients often find body composition motivating, since it shows change during plateaus. Clinicians should explain limits clearly, since accuracy varies across devices and body types.

Vital signs and physical exam checks

Blood pressure belongs in the baseline set because it changes early with weight loss. Clinicians often confirm technique and cuff size, since those details can distort readings. Heart rate, lung exam, and basic abdominal exam can add safety context. Snoring, neck circumference, and daytime sleepiness can raise concern for sleep apnea.

Foot exam and neuropathy checks matter more for diabetes risk, while labs often confirm that risk. Clinicians also note edema, since fluid retention can mimic rapid weight change. A physical exam helps clinicians decide whether they need targeted endocrine evaluation. This step also creates a reference point for future symptom changes.

Baseline lab panel: the core set commonly ordered

Blood sugar status

Most baseline panels include HbA1c, fasting glucose, or both. A1c reflects average glucose exposure across roughly two to three months, while fasting glucose captures one morning snapshot. The CDC Diabetes Testing guidance lists commonly used ranges in a format patients can understand. One concise reference line states, “Prediabetes: 5.7–6.4% … Diabetes: 6.5% or above.”

A1c can mislead in a few situations, so clinicians interpret it in context. Anemia, recent blood loss, and some hemoglobin variants can shift A1c results. A clinician may lean on fasting glucose or an oral glucose tolerance test when uncertainty persists. When results conflict with symptoms, clinicians often repeat testing under standardized conditions.

Lipid profile

A lipid profile belongs in baseline evaluation because it quantifies cardiovascular risk. Triglycerides can rise with insulin resistance, while HDL often falls. LDL contributes to long-term plaque risk, and baseline levels guide overall risk discussions. Clinicians often prefer consistent testing conditions, since meals and timing can shift triglycerides.

Many people expect cholesterol changes immediately, yet lipids often shift after sustained changes. Weight loss can lower triglycerides early, while LDL response varies by genetics and diet pattern. Baseline lipids help track direction and magnitude over time. A clinician can also calculate 10-year risk when age and history fit. That risk conversation supports health goals without obsessing over scale alone.

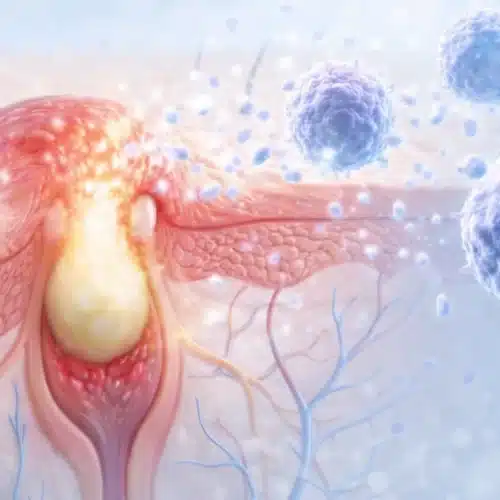

Liver enzymes and metabolic liver risk screening

Liver enzymes often appear in baseline labs because metabolic liver disease frequently overlaps with obesity. ALT and AST can provide a practical starting signal for liver stress, while clinicians interpret them alongside risk factors. A plain-language explanation appears in MedlinePlus liver function tests, which describes what a “liver panel” measures. The page notes, “Liver function tests (also called a liver panel) use a sample of your blood to measure several substances made by your liver.”

ALT and AST do not confirm fatty liver alone, so clinicians avoid oversimplifying results. Some people develop metabolic liver disease with normal enzymes, so clinicians also weigh diabetes risk, alcohol exposure, and medication history. A careful baseline helps identify who needs further evaluation, while it avoids blanket imaging for everyone. Repeat testing under consistent conditions often clarifies whether elevation reflects a trend or a temporary bump.

Weight loss can improve liver fat and inflammation, which makes baseline data useful for motivation. Clinicians also ask about recent illness and unusually intense exercise, since both can nudge enzymes upward. Patients benefit when the team explains what labs can show and what they cannot. That clarity reduces anxiety and keeps follow-up testing focused. The baseline then becomes a practical reference point rather than a label.

Kidney function and electrolytes

Clinicians often include creatinine, eGFR, and electrolytes in baseline testing. These values support safe planning, since hydration shifts and certain therapies affect kidney handling. Potassium and sodium abnormalities can point to medication effects or underlying disease. Baseline kidney function also matters for people with diabetes risk, since early kidney disease can remain silent.

Creatinine reflects filtration but also muscle mass, so clinicians interpret results carefully. Dehydration can raise creatinine temporarily, while rehydration can normalize it. A stable baseline helps compare later labs under similar conditions. People who use NSAIDs often benefit from kidney review, since chronic use can affect renal function. Clinicians can discuss hydration strategies without turning the visit into a meal plan.

Complete blood count

A CBC can reveal anemia, infection signals, or platelet abnormalities. Fatigue often drives weight concerns, while anemia can drive fatigue without relating to weight. Baseline hemoglobin helps contextualize exercise tolerance and shortness of breath. A CBC can also help interpret A1c when anemia or blood disorders exist.

Clinicians may add iron studies when CBC suggests microcytic anemia. Heavy menses, low iron intake, and gastrointestinal blood loss can contribute. That evaluation matters because fatigue can derail follow-through with healthy routines. People often blame motivation, while physiology tells a different story. A baseline CBC can support a more compassionate care plan.

Baseline labs that are situational, not automatic

Thyroid screening as a baseline checkpoint

Thyroid testing often appears in initial evaluation because hypothyroidism can mimic weight-related symptoms. Many clinicians start with TSH as a screening test, then add free T4 when TSH suggests dysfunction. Patients often benefit from a clear boundary between screening and treatment planning. This page stays focused on baseline screening rather than the full thyroid treatment pathway.

Baseline thyroid testing helps rule out a true contributor, while it avoids confusing normal variation with disease. Clinicians also avoid using thyroid hormones for weight loss when thyroid function looks normal. A targeted approach prevents unnecessary follow-ups triggered by borderline results. Clear communication also reduces stigma and self-blame around symptoms.

Micronutrient status when history suggests risk

Clinicians sometimes check vitamin B12, vitamin D, folate, or iron markers based on history. Bariatric surgery history, restricted diets, chronic acid suppression, and heavy menstrual bleeding raise suspicion. A baseline helps when symptoms overlap with fatigue, weakness, or poor concentration. Clinicians prioritize these tests when they see a plausible mechanism.

Vitamin D deficiency appears common, yet clinicians usually treat it as a health optimization step, not a direct weight lever. B12 matters when someone uses metformin or follows vegan patterns, since low B12 can affect energy and nerve function. Iron deficiency can blunt exercise tolerance and cognitive focus. Baseline correction can improve wellbeing, which supports engagement over time.

Uric acid and gout risk markers

Uric acid testing may help when someone has gout history or kidney stones. Rapid weight loss and dehydration can change uric acid dynamics, so baseline context can help. Clinicians can then discuss pacing and hydration when risk looks high. A baseline also supports monitoring if someone already carries hyperuricemia.

Many people never need this test, while some benefit greatly from knowing risk. Prior gout flares, high alcohol intake, and certain diuretics raise risk. Kidney function and uric acid often interact, so clinicians interpret them together. A thoughtful baseline can reduce avoidable flare triggers during early weight change. That foresight supports consistency.

Urine testing for metabolic risk markers

Urine testing sometimes includes albumin-to-creatinine ratio in higher-risk patients. Diabetes risk, hypertension, and known kidney disease increase the value. Early kidney changes can appear in urine before creatinine rises. Clinicians may also order a urinalysis when symptoms suggest infection or hematuria.

A urine albumin test also supports cardiovascular risk conversations. Microalbuminuria can reflect vascular stress, which weight loss and risk factor control can improve. Patients often appreciate objective markers beyond weight. Clinicians can frame results as “risk signals,” while avoiding alarmist language. A baseline then becomes a reference point for future improvement.

Special populations and add-on evaluations

Reproductive-age patients

Reproductive planning changes baseline testing priorities. Pregnancy testing may matter when pregnancy seems possible, since it affects medication choices. Menstrual history can reveal patterns that suggest hormonal evaluation, while clinicians avoid automatic hormone panels. Clinicians also ask about contraception, since some therapies require specific safeguards.

Cycle irregularity can also reflect stress, thyroid dysfunction, or polycystic ovary syndrome. Baseline screening can identify thyroid disease, while symptom patterns guide further evaluation. Clinicians may coordinate with primary care or gynecology when questions extend beyond weight management. That collaboration helps keep care integrated rather than isolated.

Suspected PCOS features

Symptoms such as irregular cycles, acne, and hirsutism can suggest PCOS. Clinicians may order labs that clarify androgen status and exclude other causes, while they avoid broad testing without symptoms. Baseline glycemic and lipid testing matters here, since PCOS can increase metabolic risk. A careful evaluation can also guide fertility discussions and long-term risk reduction.

People often blame themselves for PCOS symptoms, while physiology plays a strong role. Baseline evaluation can validate symptoms and reduce self-blame. Clinicians can frame PCOS as a cardiometabolic risk condition, not only a reproductive issue. Weight loss can improve insulin resistance and cycle regularity for many, although response varies. Baseline tracking helps show progress beyond the scale.

Sleep apnea risk screening

Sleep apnea frequently overlaps with obesity, and it can blunt energy and hunger regulation. Clinicians often screen using symptom questions about snoring, witnessed apneas, and daytime sleepiness. Baseline blood pressure and A1c often connect with apnea risk, since apnea can worsen cardiometabolic strain. Sleep screening can lead to testing referrals, while the weight plan continues in parallel.

A patient may report morning headaches, dry mouth, and unrefreshing sleep. Those symptoms can drive late-day cravings and fatigue-driven snacking. Clinicians can explain how fragmented sleep alters appetite signaling and glucose handling, while the plan targets both sleep and weight. Screening tools can help quantify risk quickly. A diagnosis also helps clarify why progress felt hard before treatment.

Prior bariatric surgery or significant GI history

Bariatric history changes baseline labs, since malabsorption and restricted intake can cause deficiencies. Clinicians often check iron studies, B12, folate, and vitamin D, while they also monitor anemia. GI symptoms such as chronic diarrhea, reflux, or vomiting also change testing choices. Dehydration and electrolyte disturbances can occur with severe symptoms.

Clinicians may add magnesium or other electrolytes when history suggests risk. Baseline labs also help set realistic goals, since surgery history changes appetite and absorption. Care becomes safer when it respects that physiology. Patients also benefit when the care team explains which risks relate to surgery and which do not. That clarity supports steady follow-through.

How clinicians interpret baseline results in a weight-loss plan

Findings that change medical urgency

Some findings require prompt action, while clinicians still keep the approach calm. Diabetes-range glucose or A1c often prompts a faster follow-up cadence and coordinated care. Very high triglycerides can raise pancreatitis risk, so clinicians address them early. Markedly elevated blood pressure can also change urgency, since cardiovascular risk rises.

Clinicians also consider symptoms alongside numbers. Chest pain, shortness of breath, or severe edema can change the plan quickly. Abnormal labs may also reflect acute illness, so clinicians often repeat testing for confirmation. That repeat strategy prevents overreaction to a transient shift. A baseline still serves as the starting line, not a verdict.

Patterns consistent with insulin resistance risk

Insulin resistance often shows up as a pattern rather than one lab. A1c trends, fasting glucose, triglycerides, and waist measures can cluster together. Clinicians then frame goals around metabolic improvement, not only weight reduction. A baseline helps track which risks improve first and which need time. Many patients find this framing more motivating than scale-only goals.

Small improvements can matter clinically. A modest A1c drop can reflect better glucose exposure even before major weight change. Triglycerides can fall with reduced hepatic fat and improved insulin sensitivity. Blood pressure can respond to early sleep improvements and improved vascular tone. Baseline patterns help make those wins visible, while the plan stays individualized.

Liver-risk patterns

Liver enzymes require context, since many factors influence them. Persistent ALT elevation can suggest metabolic liver disease, while clinicians also consider alcohol, hepatitis, and medication effects. Some people show normal enzymes despite meaningful fatty liver, so clinicians rely on risk factors too. Obesity and diabetes risk often push clinicians toward further risk stratification when suspicion rises.

Clinicians often use follow-up testing to confirm a trend. A single elevated ALT after a viral illness may normalize later. A persistent pattern may lead to fibrosis risk scoring or imaging referral. Weight loss can improve liver fat, yet clinicians also look at lipids and glucose control. Baseline liver context helps monitor improvement responsibly.

When endocrine rule-out testing fits

Endocrine disorders rarely explain obesity on their own, yet clinicians still test thoughtfully. Thyroid screening belongs in baseline evaluation, while broader hormone testing depends on clinical suspicion. Broad testing without symptoms can produce confusing results that do not change care. Clinical suspicion often comes from specific features, not general fatigue.

Easy bruising, proximal muscle weakness, purple striae, and unexplained fractures can raise concern for Cushing syndrome. Certain medications also confound testing, so clinicians document steroid exposure carefully. A targeted approach protects accuracy and reduces false positives. Patients usually appreciate testing that follows clear reasoning, since it feels fair and transparent.

What patients should bring to make the first visit efficient

Records matter because they prevent duplication and reduce delays. Recent lab reports help clinicians compare trends rather than starting blind. A current medication list supports safe interpretation and avoids missed interactions. Home blood pressure readings can add real-world context, since office readings sometimes run high. If a patient uses a wearable, sleep and activity summaries can provide useful baseline context.

A short symptom timeline can also help. People often forget when fatigue started, when weight changed, or when sleep worsened. A simple list of major life changes can add clarity, since stress and schedule shifts affect physiology. Patients often worry about judgment, while clinicians usually value honesty over perfection. Accuracy at baseline helps every step later.

3 Practical Tips

Prepare for fasting labs with consistency

Fasting labs work best with predictable conditions. Aim for an overnight fast, while you still drink water for hydration. Avoid heavy alcohol the night before, since it can alter triglycerides and liver enzymes. Skip unusually intense workouts right before blood draw, since muscle stress can affect some labs. Ask the clinic which tests truly require fasting, since protocols vary by panel.

List every supplement and “shot” used recently

Supplements often hide in daily routines, so a written list helps. Include energy boosters, hair and nail products, and “hormone support” blends. Mention any injections or peptide products, since they can confuse interpretation. Clear documentation protects accuracy and reduces repeat testing. Clinicians can then interpret results with fewer unknowns.

Bring one week of real life context

A realistic week helps clinicians understand patterns without blame. Note sleep timing, shift changes, and the most common meal timing. Record any major stress spikes, since stress can disrupt sleep and hunger. Keep it simple, since perfect logs rarely reflect real life. A baseline works best when it reflects reality.

How baseline data becomes the starting line for progress tracking

Which metrics usually change first

Some markers respond quickly to early changes, while others need time. Blood pressure can improve early, especially with better sleep and reduced sodium. Fasting glucose can shift within weeks as insulin sensitivity improves. Triglycerides often respond faster than LDL, although responses vary across individuals. A baseline makes these early improvements visible, which supports motivation.

A1c typically changes more slowly, since it reflects longer-term glucose exposure. Clinicians often schedule follow-up A1c testing after enough time passes for meaningful change. Liver enzymes can improve as liver fat decreases, although clinicians confirm trends with repeat testing. A baseline supports realistic expectations, which reduces disappointment. Progress often shows up in health markers before it shows up on the scale.

A simple reassessment schedule framework

Clinicians usually tailor retesting to risk level and initial results. Normal baseline results may warrant longer intervals, while abnormal results call for shorter intervals. Some clinics use structured checklists for baseline and follow-up tasks, which keeps care consistent. One example appears in the NICE initial assessment checklist guidance, which lists baseline measurements and investigations driven by history and examination.

Glycemic status often drives timing because it relates to diabetes risk and clinical decision-making. Lipids may follow after stabilization, since short-term shifts can mislead. Liver enzymes often get rechecked when elevations appear, since clinicians want trend confirmation. Kidney function may warrant closer follow-up when diabetes risk or medication use raises concern. A structured schedule helps patients avoid “random lab chasing.”

Avoiding misleading comparisons

Lab numbers fluctuate for normal reasons, so clinicians compare like with like. Illness, dehydration, and major sleep disruption can shift glucose and electrolytes. A lab taken after a vacation week may not represent typical physiology. Medication changes also matter, so clinicians document timing carefully. A baseline works best when it reflects a stable, typical week.

This quick reference table shows common baseline-lab “gotchas” that can skew results, along with simple steps that help keep your first set of labs reliable. It adds clarity on timing, short-term factors, and preparation details that often get missed during an initial assessment.

| Baseline Lab or Measure |

Common Factor That Can Skew the Result |

What It Can Look Like |

Simple Prep Step to Improve Accuracy |

When to Mention It to the Clinic |

| Fasting glucose |

Short sleep night, late heavy meal, or early-morning stress |

Higher-than-expected reading despite usual habits |

Keep a normal dinner and aim for a consistent bedtime before the draw |

At check-in if the prior night was unusual |

| HbA1c |

Recent blood loss, anemia, or iron deficiency |

A1c that does not match fingersticks or symptoms |

Tell the clinician about recent anemia treatment or heavy bleeding |

Before labs get ordered, since it can change test choice |

| Triglycerides |

Alcohol within 24–48 hours or a very high-fat meal |

Temporary spike that looks more concerning than baseline risk |

Avoid alcohol and keep meals typical for 1–2 days pre-draw |

At scheduling if a holiday or travel week just happened |

| ALT/AST (liver enzymes) |

Hard workout, viral illness, or dehydration |

Mild elevation that may disappear on repeat testing |

Avoid unusually intense exercise for 24–48 hours and hydrate normally |

At check-in if you recently felt sick or trained hard |

| Creatinine/eGFR |

Dehydration, low fluid intake, or recent high-protein day |

Slight rise that can look like reduced kidney function |

Drink water as usual and avoid extreme dietary changes before the draw |

At scheduling if you tend to run dehydrated |

| TSH (thyroid screening) |

High-dose biotin supplements or recent steroid use |

Results that do not fit symptoms or prior history |

Bring a complete supplement list and note any steroid courses |

Before blood is drawn, so the team can advise timing |

| Waist circumference |

Inconsistent tape placement or measuring after a large meal |

Bigger swings that reflect technique, not true change |

Measure at the same landmark and time of day each visit |

During vitals, ask the team to note the measurement method |

Consistency also supports better interpretation of body composition measures. Hydration changes can shift bioimpedance readings, which can confuse progress tracking. Waist measurement changes can vary with technique, so consistent measurement points matter. Patients can ask clinics to repeat measures using the same method each visit. That approach reduces noise and highlights true change.

FAQ

Do I need to fast for baseline labs?

Some panels require fasting, while others do not. Clinics often prefer fasting for triglycerides, since meals can change them. A1c does not require fasting, while fasting glucose does require it. Ask the clinic which tests they plan, since protocols vary. Water usually helps, since dehydration can skew results.

If my A1c looks borderline, does the approach change?

A borderline A1c can signal prediabetes, which can influence goal setting. Clinicians may track glucose markers more closely and emphasize metabolic targets. Many people see improvements with sustained weight loss and supportive lifestyle changes. A clinician may also coordinate with primary care when results suggest higher risk.

Why would a clinic order liver enzymes for a weight-loss program?

Obesity often overlaps with metabolic liver disease, so baseline enzymes can help risk assessment. ALT and AST can flag liver stress, while they do not diagnose a specific condition alone. Clinicians often repeat testing to confirm persistent elevation. Risk factors and symptoms guide whether imaging becomes appropriate.

Is thyroid testing always included in baseline workup?

Many clinicians include thyroid screening because hypothyroidism can mimic weight-related symptoms. Clinicians usually start with TSH, while they add free T4 when TSH suggests dysfunction. This baseline step supports accurate planning, while treatment decisions belong in deeper thyroid-focused care. Clear screening also helps reduce unnecessary worry about “mystery hormones.”

Next step: turning baseline results into a personalized clinical roadmap

A good assessment links lab findings to achievable health goals. Baseline data can highlight which complications deserve priority, while it also supports realistic expectations. At Fountain of Youth in Fort Myers, our staff stays on top of evolving baseline assessment practices, so testing remains purposeful and current. Questions? We are here to help—give us a call at 239-355-3294.

Baseline labs can feel intimidating, yet they often bring relief by replacing guesswork with clarity. When people understand their starting line, they can measure progress in more than one way. A structured baseline also helps patients advocate for themselves in future care. The best plans use these results as direction, then they focus on steady progress.

Establishing a clear biological starting point is the most critical step in designing a safe and effective weight loss protocol. This diagnostic phase allows clinicians to identify underlying issues like hypothyroidism and weight gain that could otherwise hinder progress. The resulting data informs every other aspect of your journey, from personalized meal planning to the development of a low-impact exercise plan. Understanding your baseline health also aids in side effects and risk management, ensuring that chosen therapies are appropriate for your physiology. For those who may not be candidates for traditional therapy, labs help uncover prescription options beyond GLP-1. Once treatment begins, adherence systems provide the necessary structure to follow through on clinical recommendations. Addressing the relationship between mental health and weight from the outset creates a more holistic path to wellness. Finally, these initial metrics serve as the benchmark for all future follow-ups and maintenance, allowing you to see measurable improvements in your metabolic health.

Medical review: Reviewed by Dr. Keith Lafferty MD, Fort Myers on January 5, 2026. Fact-checked against government and academic sources; see in-text citations. This page follows our Medical Review & Sourcing Policy and undergoes updates at least every six months.